These men are ghosts. — Adolf Hitler

The face of the Third Reich was from the beginning a double face. That principle of duality which was Hitler's essential tactical device, which characterized the regime's initial rise to power and meant that all structures combined terror and legality, strict order and chaos, Machiavellian open-mindedness and dull witted instinctiveness, was also expressed, quite overtly, in physiognomic terms. The type of the 'Unknown SS Man', the muscular but frankly heartless and brainless hero forever tearing chains apart and smashing barriers on countless posters — for example; those by the designer Mjoelnir — was counterbalanced by the figure of the respected privy councillor of conservative stamp, who 'placed himself confidently behind the new leadership'. The strong-arm and the respectable elements marched side by side and supplemented each other. While the half-light of the background was populated by wholly criminal characters such as troop-leader 'Rubber Leg' from the Berlin Central District or the Neuköllner SA unit which, with underworld self-confidence, called itself the Ludensturm, the 'Gang of Rogues', (1) the regime presented a legalistic facade of reassuring types who guaranteed its middle-class respectability: Konstantin von Neurath, Hjalmar Schacht, Franz von Papen.

It needed them especially at the beginning. The National Socialist leadership had realized that a complicated modern administrative system was not to be overcome in open attacks in the street, but rather by the gradual capture of key points in the political, economic and bureaucratic organization; now it defined its own steps towards the conquest of the state, not as a revolutionary break, but as the final attainment of the true nationalist Germany which had remained hitherto suppressed, or at least had failed to take over government. What was presented by skilful propaganda and enthusiastically acclaimed as the emergence of the people, the rebirth and liberation of the national honour, bore in reality all the marks of a revolutionary change.

A multitude of factors enabled this aspect to be widely and effectively concealed at least at the beginning. Of crucial importance was the fact that the National Socialists were able to play with overwhelming success upon the weakness of character and susceptibility to totalitarianism of the spokesmen of national conservatism, who allowed themselves to be thrust into the foreground and exploited as figureheads in the great deception. In the wider sphere of the conservative middle class the decision to support the 'national cause' did not spring solely from blindness and opportunism; but also from the short-sighted argument that by collaborating they could 'avert something worse' and block Hitler's path to autocratic rule. This complex of illusions and fallacies contributed essentially to the success of the National Socialist bid for power, but what weight it carried was the result not least of the collaboration of leading representatives of conservatism, and for them these considerations possessed no significance whatever. Their personal support gave a spurious appearance of legality to the ecstatic emphasis upon the nationalist element; they were men of straw in the seizure of power, who distracted attention from the terrorism and violence, providing a murderous enterprise with an honourable veneer. Their attempt, based on an over-estimate of their own importance, to enlist the regime in the service of their own aims, in themselves not very dissimilar from those of the National Socialists, lasted only until Hitler knew that he was firmly in the saddle. Then they found themselves eliminated, and for some humiliating dismissal was their first intimation of the mistake they had made in entering into this partnership.

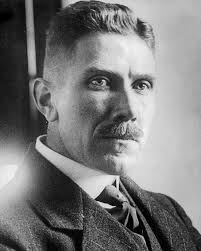

With all his self-righteous lack of conscience Franz von Papen, of course, never achieved this insight. Nevertheless particular circumstances made him the representative of these nationalist conservative circles: his historical role itself and the characteristics and qualities which shaped him for it; his claim, in which he persisted throughout, to belong to the 'upper stratum authorized by history'; his unhesitating identification of the interests of his class with the interests of the state; his socially reactionary attitude, which he disguised behind a pseudo-Christian vocabulary; his sprinkling of monarchist ideas; his nationalistic jargon; his tendency to think in long-outdated categories; in short, his anachronistic profile and finally the hint of caricature which hung over his whole person. All this makes him a perfect model of that type of the ruling class which on 30th January 1933 placed itself at the disposal of National Socialism, because with an almost unparalleled blindness it imagined itself to be once more called upon by history to assume leadership.

Franz von Papen came of an old Westphalian noble family, had served in a feudal regiment, and achieved a certain publicity in 1916, during the First World War, when he was expelled from the United States for conspiratorial activities while military attache. While crossing to Europe he allowed important documents relating to his secret service activities to fall into the hands of British intelligence, a piece of carelessness which seemed typical, for a similar misfortune befell him a little later on the Turkish front. A few years after the end of the war he entered politics and became a member of the centre group in the Prussian Landtag, evidently as representative of the agrarian interests of his district. His marked rightist tendencies induced him in 1925 to canvass during the Reich presidential election not for the candidate of his own camp but for Hindenburg, and he found himself on several occasions in open conflict with his party, within which he enjoyed no particular influence. He was more highly thought-of among the anti-parliamentary, anti-republican right, whose representatives mourned the end of the monarchy and with it their own opportunities for prestige and influence, and who were striving for the recovery of power by means of confused, naive, reactionary and unrealistic plans.

Although unsuccessful in attempts to gain a seat in the Reichstag, Papen did achieve a certain political influence over the centre newspaper Germania. Together with the industrialist Florian Klockner he acquired a majority of the shares in the paper and eventually became chairman of its management committee. His marriage to the daughter of a leading Saar industrialist had brought him both a considerable fortune and good connections with industry. If we add to this the fact that he had links with the high clergy as a Catholic nobleman and contacts with the Reichswehr as a former General Staff officer, we have the picture of a man who supplemented his personal inadequacies with a network of connections and achieved some importance in the intermediate realms of politics as the point of intersection of numerous interests. Occasional lectures to rightist clubs and cliques, as well as newspaper articles, show him as a man who addressed himself with a forceful superficiality to a conservatism which labelled itself national, above parties and Christian. In fact, this conservatism acted on behalf of massive interests, with class-political, industrial and agrarian basis, and in advocating an authoritarian regime linked nostalgia for the past with rejection of the present. Papen had practised politics more in the dilettante form of establishing and exploiting contacts and had no experience of administration or leadership when on 31st May 1932 he was appointed to succeed Bruning as head of a crisis-shaken modern industrial state. The change of government was based solely on personal whim and Papen's appointment, the then French ambassador in Berlin, Andre,Francois-Poncet, wrote,

'was at first greeted with incredulous amazement; when the news was confirmed, everyone smiled. There is something about Papen that prevents either his friends or his enemies from taking him entirely seriously; he bears the stamp of frivolity, he is not a personality of the first rank. He is one of those people who are considered capable of plunging into a dangerous adventure; they pick up every gauntlet, accept every wager. If he succeeds in an undertaking he is very pleased; if he fails it doesn't bother him.' (2)

Precisely these qualities no doubt contributed to the making of a Chancellor out of a political nonentity. The power groups that had brought about Bruning's downfall and now arranged this appointment may have been less interested in Papen himself than in his political position between centre and right.(3) They evidently saw in him, with his insouciant activism, a suitable front man for the elimination of the severely damaged parliamentary system in the interests of an authoritarian class regime. Furthermore the decision of General von Schleicher, who as Hindenburg's confidant and 'Chancellor-maker' very largely controlled this affair, was undoubtedly greatly influenced by the idea that the inexperienced Papen, with his concern for outward trappings, would find his vanity satisfied by the post itself and the representational functions connected with it, and for the rest would prove a pliable tool. This was very much to the liking of Schleicher, who combined ambition with an aversion from publicity. When astonished friends protested that Papen had no head for administration, the General replied,

'He doesn't need a head, his job is to be a hat.' (4)

If Schleicher imagined that the real head of the new government was going to be himself, he was soon disappointed. Lacking any natural respect for the traditions and problems of his high office, Papen took up his duties, and it was no mere polemical exaggeration when his opponents repeatedly accused him of carrying over into politics the outlook of a riding gentleman: he himself confirmed the parallel in his memoirs when he advocated riding as a school for political character-building on the grounds that it offered 'no concern for broken bones'.(5) Again and again he acted on his basic idea that a difficulty, like an obstacle confronting a rider, was overcome once one had easily and boldly jumped it. In any case, he broke free from his dependence upon Schleicher and began, with growing self-confidence, to pursue his own aims and the interests of those circles whose representative he was, so that the General was forced to the admission:

'What do you say to that, Franzchen has discovered himself!' (6)

The new Chancellor owed the opportunity of evolving a policy of his own mainly to the backing of the aged Reich President, who took a fatherly pleasure in the adroitness and frivolous charm of Papen, the man of the world. The mutual attraction sprang from their respective characters and matched the close relationship between their prejudices, political tendencies and interests, in which, across the generation gap, a sterile conservatism bogged down in out-of-date ideas found expression.

'Both had in common, in spite of the great age difference, the fact that they failed to recognize that times had changed,' (7)

and in particular, the fact that they ignored the social problem and any possible solutions, or evaded the problem with hollow phrases revealing patriarchal and aristocratic attitudes. Their anachronistic thinking still reflected the imperial period's false alternatives of socialist or nationalist, in which every group to the left of centre was tainted with the odium of anti-patriotism; it blindly overlooked the fact that the dominant antithesis of the age had long been between democratic and totalitarian. The aim of achieving, in an imaginary halfway house between these two, something expressed by the formula of a 'constitutional dictatorship', a new state 'between democracy and totalitarian dictatorship', was nothing but the thoughtless and confused coupling together of contradictions. It made no sense but in the course of historical evolution had the effect of preparing the way structurally and psychologically for Hitler.(8) When Walther Schotte, the ideologist of Papen's reformist idea, asserted that the new state

'must be a strong state free from sectional interests, just in itself, independent of the parties',

each of these formulas was merely a lofty synonym for a demand for domination on the part of the social classes which stood behind this project. A 'strong state' meant merely an anti-liberal state; 'free from sectional interests' meant free from any right of the trade unions or any other public institutions to participate; the demand for justice was intended to legitimize the ostensibly 'naturally' determined claim of these classes to have the state at their disposal; and 'independent of the parties' — really meant independent of the left. It has been rightly pointed out that it was no coincidence that many representatives of this brand of conservatism

'saw the Middle Ages as their ideal, not only because at this period men were rooted in a firmly established order and had faith, but also because political rights were at that time possessed only by the few'.(9)

From the socially reactionary emergency decrees of mid-June 1932, which gained the administration the mocking title 'the cabinet of barons', through the coup d'etat against Prussia, to the openly proclaimed intention to bring society back to its class foundations and wipe out the 'so-called achievements of the Revolution', (10) every measure of Papen's administration betrayed a fixation with out-of-date ideas. Its aims and programme gained the support of only a minute fraction of the public, whose personal interests they represented; otherwise the regime remained highly unpopular. If Papen was appointed Chancellor in the hope of replacing the SPD's toleration of the government's line by toleration on the part of the NSDAP, this hope quickly proved ill-founded. Even the hazardous credit which the government extended to the Hitler party, ruthlessly fighting its way to power by the method of civil war but nevertheless a good nationalist and anti-liberal party, did not bring it the hoped-for period of toleration. Amid loud expressions of public disapproval and supported only upon the narrow foundations of the President's trust, it slipped into isolation. No other cabinet in German parliamentary history ever suffered, like this one, a defeat by 42 to 512 votes. Astonishingly enough, in spite of growing failures, the Chancellor lost all his former doubts (11) as to his fitness for government office. Only tremendous pressure by Schleicher compelled him to resign at the end of 1932, just as he was about to carry out a large-scale coup. In a touching scene, which conveyed to the departing Chancellor the certainty of his undiminished influence at the presidential court, Hindenburg handed him his photograph with the inscription 'I had a comrade'. (12)

Papen used his influence for an altogether disastrous intrigue. In spite of all assertions to the contrary, it was he who took the initiative in establishing an alliance with Hitler, who was already beginning to despair of attaining power. Any hesitations he may have had about entering into this suicidal partnership were doubtless swept aside by his natural recklessness, his arrogant assumption of his own right to lead, and an itch for revenge upon his rival Schleicher, now Chancellor in the new cabinet. At all events, the offended Papen cleared away the last personal obstacles to a partnership between the nationalist right and the NSDAP, thereby restoring the Harzburg alliance, but this time with real chances of achieving power.(13) The fragility of this alliance had already been clearly demonstrated several times, but no experience could cure Papen, Hugenberg or the German nationalist circles around them of their illusions. The curious mixture of personal vindictiveness, blindness and arrogance which had brought about this alliance shows how far the leading elements in German conservatism had come in the long process of degeneration, and it is undoubtedly more than a coincidence that its thinking led it to Hitler.

Agreement went far beyond tactics, not merely negatively in a common antagonism to democracy, liberalism and all freedom, but also positively in the vision of an authoritarian, nationalist class order with militarily orientated structures and the idea of a national community welded into a single disciplined entity. The nationalist and the National Socialist visions only gradually parted company.

'Papen spoke on the radio,' Goebbels noted in his diary in August 1932. 'A speech that sprang from beginning to end from our ideas.' (14)

Long since shorn of all humanist and religious values, but also devoid of the critical consciousness of tradition, the position of the conservatives no longer had any vitality or any ideas relevant to the future. It contained nothing but the rigid demand, linked with the memory of past privileges, to entrench and wait for the hour to strike. Such conservatism could boast no intellectual or practical result that was not lost in the catastrophe it brought about. It stood immobile on all fronts; defensively it staked everything on the negation of the Revolution of 1789 with its political and social consequences, while offensively it had nothing to show but the concept of the nationalist authoritarian state; and whatever it presented as conservative ideology, the overwhelmingly predominant ideas were nothing but variations on these two uninspired motifs.

This was the point at which the national conservative and the National Socialist ideologies met. It was not so much the voters' lack of discrimination, as Papen later reproachfully claimed, as the largely identical points of departure which led the greater part of the population to vote for Hitler instead of for the 'conservative programme'.(15) Strictly speaking, all attempts to differentiate the conservative ideology and programme from the National Socialist failed, and the verbiage expended in the-effort reveals precisely what it seeks to conceal.

'If I were not a German Nationalist, I should like to be a Nazi,' Oldenburg-Januschau declared at a public meeting (16).

A remark of this kind tells us more than the most extensive analysis could about the degeneration of the conservative spirit in Germany. Fundamentally, he and his kind admired the consistency and ruthlessness of the National Socialists, and only the more helpless and stilted manner in which the German Nationalist movement expressed its aims distinguished it from the other camp. Whereas Hitler was able to set masses in motion, the turgid conservative proclamations, together with the recurrent assumption of arrogant superiority, prevented their having any effect whatever. In January 1933 as in Harzburg, a crucial attraction of the alliance with Hitler was the hope that the 'officers without an army' in the ranks of the NSDAP might at last come to lead those masses that had refused their allegiance to the conservative cause as such.(17) The hate-filled demagogy, naked barbarism and evil impulses that filtered up to the top were indulgently ascribed by these gentlemen to what they called the basically good-natured young and to the movement's excessive revolutionary impetus, which they confidently expected to tame. With such a wide range of agreement on practical points, they believed the points of disagreement were mainly-about differences of method, and the forms in which the claim to social exclusivity was made.

That even here the divisions crumbled away is shown by the reaction to the Potempa murder case. In this Upper Silesian town, in summer 1932, five SA men dragged a Communist worker out of bed after a drinking bout and literally trampled him to-death in front of his horrified mother. When the murderers were condemned to death, it was not only Hitler and the other National Socialist leaders who declared their solidarity with them, but also various conservative groups, including the Stahlhelm and the Konigin Luise Bund, who petitioned for clemency to the Reich President, (18) while Papen, as Chancellor, hastened to put the pardon into effect. Hermann Rauschning wrote, vividly summing up the conservative Nationalist — National Socialist convergence:

In judging violence there is no contradiction between reaction and revolution. Hence the German Nationalist viewpoint was in essence merely a politically more moderate but fundamentally equally as nihilistic a doctrine of force as that of the National Socialists. This is the basic reason for the combination of bourgeois nationalism, of reactionary pseudo-conservative forces with revolutionary dynamism, and it is the essential reason for the later capitulation of those bourgeois forces before National Socialism, because the more consistent expression of any viewpoint always triumphs over the more irresolute. There had for a long time been no conservatism left in Germany, but only a bourgeois form of the doctrine of force coexisting with the consistent revolutionary form. (19)

It was in fact widely believed in the conservative camp that they all, including the Hitler party, belonged to a great common movement with great common aims. Edgar Jung, one of the spokesmen of conservatism and a close colleague of Papen, stated in 1933, in complete agreement with this view, that the 'German revolution' had conservative roots alongside its National Socialist roots.(20) No doubt this comment had the tactical aim of stating the conservatives' own claim to a part in the fashioning of the new state; but it confirms the thesis advanced here, and is moreover an expression of the illusory conviction of their own value that finally led the conservatives around Papen, Hindenburg and Hugenberg to the fatal government reconstruction of 30 January 1933. Despite all warnings, Papen, Vice-Chancellor in the new cabinet, arrogantly declared,

'What are you worried about? I have Hindenburg's confidence. In two months we shall have Hitler squeezed into a corner so that he squeaks.' (21)

Even if both sides entered the alliance of 'national coalition' with treacherous intentions, it soon emerged that only one side was resourceful, skilful and unscrupulous enough to turn this 'system of perfidy'(22) to its own advantage. In spite of the composition of the cabinet - eight German Nationalists to only three National Socialists - the former were unable to resist

Hitler's power lust, pursued by himself and his followers with every means at their disposal. Many conservative interests were simply seized and swept away by adroit manipulation of the current of national rebirth. All the nervous efforts of Papen and his aides to assert their own image beside that of the National Socialist mass movement were simply not taken seriously by the public, in fact were totally disregarded, so that support for the new state was expressed almost exclusively as support for the dominant personality of Hitler. Another weakness of the German Nationalist members of the cabinet was that they were unable to present a united front to the National Socialists, who themselves acted in close and systematic concert. Hence in Hitler's lightning conquest of power every step led to success, while the other side lapsed first into paralysis and then into disintegration. Hindenburg was led by the nose, Papen tricked, the Länder forced to toe the line, while the Reichswehr leadership swung over into Hitler's camp and so was no longer available as a bastion for a conservative counter-attack. Papen and his friends owed it solely to a magnanimous leadership confident of victory that for a little while longer they were allowed to believe they had achieved their hopes; for the more Hitler secured for himself the true positions of power, the more he left the symbols of power to the others together with the illusion that their cause was advancing. As late as April 1933 Hugenberg called himself and the German Nationalist groups guarantors for the order and legality of the 'German resurrection', dismissing National Socialist excesses with the comment that you couldn't make omelettes without breaking eggs.(23) The summit of conservative blindness and error was reached on 21st March 1933, the day of the carefully staged ceremonial opening of the first Reichstag of the Third Reich, which brought together partners in a supposedly common cause at the tomb of Frederick the Great at Potsdam in a welter of national emotion; the deceived and the triumphant deceivers, Hindenburg and Hitler, Papen and Goring, Hugenberg and Goebbels. Immediately afterwards

'the veil of illusion was torn, affording a full view of the reality of the National Socialist autocracy'.(24)

With the State Act of Potsdam, which National Socialist propaganda celebrated as the 'hour of birth of the Third Reich',(25) together with the Enabling Law passed two days later, the conservative partners in the cabinet had largely fulfilled their function in the National Socialists' scheme for seizing power: namely, to cover up the break that marked the transition from the constitutional to the illegal state and at the same time to foster in the still hesitant, vacillating mass of the people the misconception of the common cause of all Germans under the 'Chancellor of Unity', Adolf Hitler. There is no doubt that up to the collapse of their deluded hopes, and in some cases even beyond it, the conservatives performed their part perfectly. Papen's assurance that in the electoral campaign prior to 5th March 1933 he had sufficiently proclaimed the distance between Hitler and his own camp by his reference to the coalition character of the government was useless, and it is contradicted by the observation of his close ally Edgar Jung that on this day

'real government elections were carried out in Germany for the first time'.(26)

He also hoped that by stressing their common interests he would benefit from thatwave of new confidence which was so patently carrying Hitler aloft. There were in fact very few members of the nationalist-minded bourgeoisie who were not led astray by the slogans of unity and the intoxication produced by the apparent realization of the 'community of the nation'; but the demonstrative fraternization between the spokesmen of conservatism and the National Socialists confronted many of them with a genuine dilemma and finally, as a national 'duty', they accepted trends which they regarded with aversion. Among the documents of the Nuremberg trials is the diary of a senior Bavarian judge from the years 1933-4, who was clearly fully aware of the terrorist, anti-legal and anti-cultural character of National Socialism and yet joined the party and even the SA in order to place his energies at the service, not of the NSDAP, but of the 'movement for national rebirth'.(27)

In the same way holders of public or semi-public office were not infrequently willing actively to collaborate with the new order with a view to damping down the National Socialist Party's extremism and moves towards exclusive rule. In so far as they exercised any moderating influence at all, this was entirely in line with the aims of Hitler, who in the stage of transition to full power was particularly dependent upon the specialist knowledge and tutelage of the bureaucratic, technical and economic elite in order to maintain the fiction of the regime's legality.

It bears all the marks of brazen impudence when Papen denies all understanding of this problem, which he himself largely caused, and when he of all people, who did more than anyone else outside the Nazi Party to help Hitler to power, reproaches the German people with 'lack of intelligence' and 'intellectual laziness' because they did not show greater reserve towards Hitler and National Socialism.(28) He himself was for a long time content, on his own admission, to pin his hopes on the 'work of education in the cabinet'. Notwithstanding all the acts of resistance which he subsequently claimed, he announced his own reservations at a rather late stage, when Hitler had long since seized power and scornfully shouted after the partners he had brusquely dismissed that they were bourgeois

'who choose a dictator for themselves, but on the tacit conditions that in reality he will never dictate'.(29)

Papen's famous Marburg speech of 17th June 1934, written by Edgar Jung, which occupies so much space in Papen's apologia, was not so much the outcry of a sense of justice outraged by the aims and methods of the National Socialist conquest of power as the outcry of an infuriated accomplice finally brought to realize that he had no chance of putting his own plans into effect and that if he had been given any role at all it was purely as a decorative element in a state which, after a fourteen-year interregnum, he considered as belonging once more to himself and his class and which he had intended to govern. It was not least this claim behind Papen's words that caused Hitler's harsh reaction to the speech and gave the bloodbath of 30th June 1934, a fortnight later, its double intention. We should still be blinded by National Socialist pronouncements if we looked upon the events of that day as solely a showdown between Hitler and Rohm, between party and SA. Far beyond this, the blow was simultaneously aimed at the last remaining claims to power of the conservative and bourgeois interests. Papen himself was kept under house arrest for a time, while two of his closest colleagues, one of them Edgar Jung, were murdered, so that the Vice-Chancellor 'stood like a melancholy king skittle among blood and corpses'.(30) It is true that like a man of honour he thereupon offered his resignation, but he did not follow the path to resistance which a considerable group from the conservative camp took after this moment of disillusionment. On the contrary, a few weeks later he again offered his services to Hitler, the murderer of his friends, and one wonders whether this decision was the easier because Hitler was at the same time the murderer of his bitterest enemy, General von Schleicher.

Ambition and an insatiable self-importance, however, undoubtedly played a greater part in Papen's decision. He found it intolerable, one of his conservative cabinet colleagues later wrote,

'not to be in the game, even if he did not like his fellow players'.(31)

Ostensibly after a severe inner struggle, he went to Vienna as an envoy on a special mission — to prepare the way for the Anschluss; but we have only to read what thoughts filled his mind when he was called by Hitler to know how willingly he allowed himself to be defeated in this struggle with himself.(32) Again in 1938, when for the second time one of his closest colleagues was murdered at his side, he remained willing to serve Hitler and shortly afterwards assumed the post of ambassador in the Turkish capital, as ever incorrigibly convinced that in so doing he was serving not the illegal National Socialist regime but the German Fatherland.

'The man of true spirit,' Papen declared in his Marburg speech, 'is so full of vitality that he sacrifices himself for his convictions.'(33)

But neither he himself nor German conservatism as a whole displayed the vitality that would have led them to sacrifice themselves, or even their opportunism and self-importance, for the convictions which they later claimed to have; the few exceptions do not disprove this. Instead they all fell back upon the idea of service to the Fatherland, blindly accepting as 'service to the Fatherland' service to a murderous regime that flouted the law and broke its word.

Papen's personal experience and his unusually great opportunities for true insight into events make it clear that in his cue, at least, the arguments which he produced were simply self-justification. Even if we accept that the realization he voiced at Nuremberg that Hitler was 'the greatest murderer of all time' had not come to him earlier, it involves the admission of a serious and long-standing error. In fact, Papen retained to the last his self-righteous attitude and criticized lack of intelligence, discrimination and insight on the part of others only — the German people, the Allies, and even, in a particularly shocking manner, the murdered Edgar Jung.(34) Moral insensitivity, a fundamental lack of intellectual honesty, and that class-conscious mode of thinking which dealt with the truth like a master with his servants, always made such inconsistency easy for him. Justice Robert H. Jackson, in his speech for the prosecution against Schacht, vividly summed up the contradiction in the behaviour of the conservative collaborators.

'When we ask him,' said Jackson, 'why he did not halt the criminal course of this government in which he was a minister, he says he had absolutely no influence. But when we ask him why he remained a member of a criminal government, he tells us that he hoped to moderate the programme by remaining there.'(35)

In fact this contradiction, to which, in various shapes, all later attempts at self-justification by the regime's conservative collaborators ultimately lead, cannot be resolved. It indicates at the same time the homogeneous nature of the motives which, beyond all purely personal interests, caused the majority of conservatives to cling to the alliance with Hitler regardless of humiliations: the will at any price to regain the leadership of the nation, or at any rate certain leading positions. Behind this lay the feeling of being naturally called upon to govern, which had never left them, and the trauma suffered by the loss of the state in 1918, both permeated by the outwardly denied but inescapable realization of their own weakness, which made their urge to participate as undignified as it was tenacious.

'Have you noticed how people tremble, how they try to say what will please me?' Hitler asked contemptuously in 1934, looking at Papen and the German Nationalist group.(36)

Thus the collaboration with National Socialism revealed how incompetent and utterly burnt out conservative nationalism was. No other social group failed so abysmally in face of the challenge. The case does not need to be reinforced by reference to the personal and financial support which Hitler received, in particular during the years of his rise to power, from land-owners, leaders of heavy industry and other interested parties. Some predominantly Marxist interpretations (37) unwarrantably shift the emphasis and make Hitler appear a mere front man for alien forces in the background, whereas in reality it was precisely the specific failure of German nationalist conservatism to have allowed itself, for the sake of short-sighted aims, to be misused for the purposes of others. Edgar Jung declared in 1933:

'Revolutionary conservatism is sacrificing temporal values in order to save eternal values.'(38)

The truth is that this type of conservatism had long abandoned 'eternal values' and, in its desperate and vulgar hunger for power, threw away temporal values too when it fraternised with Hitler. The lack of any feeling of personal guilt, continually evident in the memoirs of the conservative partners in the regime, may be subjectively entirely honest; it merely shows the extent to which consciousness of the existence of obligatory values had atrophied, for the degree of sense of guilt is always dependent upon the degree of consciousness of value, and only where binding norms are no longer recognized is their betrayal no longer felt.

'Dear lady, we have fallen into the hands of criminals, how could I have suspected that?'

wrote Schacht in summer 1938. (39) Actually, anyone capable of sober, uncorrupted thought would not merely have suspected this but known it without a shadow of doubt long before 1938. It was above all the loss of integrity, the intellectual corruptibility and the capacity to close its eyes that led conservatism first into Hitler's company and then inevitably into alliance with him. When a documentary film on the concentration camps and mass extermination centres of the Third Reich was shown in the Nuremberg court-room, Papen covered his face with his hands. It was more than a spontaneous gesture of horror: it symbolized an attitude. 'I did not want to see Germany's shame,' he declared later.(40) He had never wanted to see it, though he had helped to bring it about.

Any analysis of the role of Papen and the conservatism he represented must lead to indictment for his share in the rise of National Socialism, his work in preparing the way. Unembarrassed by his disastrous activities, by his speeches on the 'National Revolution' which mark him as a driving force in the coalescence of the nationalist right, by the 'high degree of responsibility for the alliance',(41) which he joyfully assumed at the time, Papen vigorously denied this historical guilt and even at Nuremberg provocatively described himself as the spokesman 'of the other Germany'.(42) Meanwhile the degree of his responsibility has been clearly demonstrated, and his transparent attempts to diminish his own part in the formation of the government of 30th January 1933 do not exculpate him, for they miss the essential point of the accusation against him, that he was the 'stirrup-holder' of the new regime. It is not on his mere attachment to Hitler, mainly from base personal motives, that the indictment of Papen rests, but rather on his preparation of public opinion for the ideals which conservatism shared with National Socialism, upon which he embarked before 1933, and his stirring up of anti-republican feeling and systematic under-mining of the constitutional structure of the Weimar state.

'History is waiting for us,' Papen cried at the end of his Marburg speech, 'but only if we prove ourselves worthy of her.'(43)

With all circumstances taken into account, even bearing in mind the resistance offered by isolated groups of bourgeois conservatives when they belatedly realized the truth, German conservatism as a whole cannot be said to have stood the historical test. For the decision to resist did not spring from a newly acquired consciousness of the binding force of a once-valid conservative idea, which had long since been devalued in opportunist manoeuvres, bargains with power and parasitic class egotism; it was a case of individual decisions the impulses to which lay 'outside ideology', so that conservatism did not even master the one task Hitler had left to it: 'to die gracefully'.(44) Ultimately it was probably the sense of its own desiccation and anaemia, together with a desperate desire for power and 'historical authority', that set German Nationalist conservatism on its downward path. It hoped, by joining with the secretly despised but at the same time admired upstart Hitler, to share in the force and vitality of the National Socialist mass movements and with its support to regain a status of which history, not without reason, had already deprived it.

'I desire a great and strong Germany and to achieve it I would enter into an alliance with the Devil,' Hjalmar Schacht once declared. (45)

But rarely in history has the old proverb proved so true, that he who sups with the Devil needs a long spoon.

As Thomas Mann remarked, however, the Devil is already present

'where intellectual arrogance is wedded to an antiquated and restricted frame of mind'(46)

This raises the question which side of the table the Devil was actually sitting in this alliance. But this is one of those questions that only grow more complicated, and finally insoluble, the longer one thinks about them.